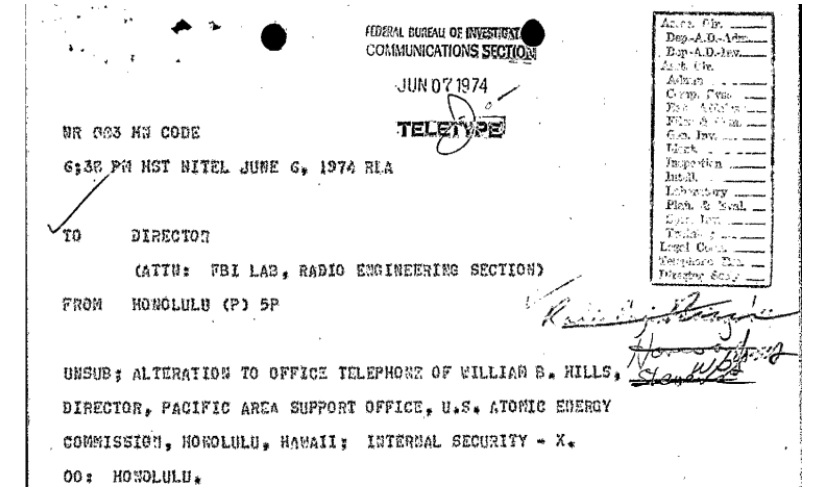

While most of the FBI’s released files on early counter-surveillance measures, or “Technical Security Surveys” as the Bureau called them, show no more cause for alarm than faulty wiring, with a few notable exceptions, one stands out as both an historical curiosity and a demonstration of why clever counterintelligence and law enforcement officers often leave listening devices in place. According to the FBI file, a few months before it was abolished, a bug was discovered in the Honolulu offices of the Atomic Energy Commission. The device would not only let someone listen in on phone calls, but any conversations held around the phone - even when it wasn’t in use.

According to the file, the bug was discovered by one Lt. Colonel Harry Tear Jr., assigned to Army counterintelligence at Fort Shafter. While performing a regular electronics sweep in June of 1974, Tear discovered a modification to the phone of Williams Hills, who was the Director for the Atomic Energy Commission’s Pacific Area Support Office, reporting to the Nevada Operations Office.

When it was discovered, the phone wasn’t being used to monitor the room. The file notes, however, that it easily could be. When connected, the phone wouldn’t just transmit the conversation being held, but every conversation in the room that happened to be in range of the phone’s receiver. They were unable to determine when it had been installed or how often it had been used, but noted that the wiring appeared to have been done professionally. They were also able to confirm that the device could pick up conversation in the room in practice, not just in theory.

The investigators were apparently unable to determine exactly how the information moved through the telephone frame room. How it was planted was just as much of a mystery. Over 100 people worked in the building, most of them working for the AEC contractor Holmes and Narver. The modified phone was on the second floor of the building, which just under 50 people, all with Q Clearance, could access it. The FBI notes that this number didn’t include the, presumably without clearances, cleaning crew, and the security team provided by the Burns Agency who had access to the floor.

The specific office’s work focused on support and logistics, meaning that little - if any - sensitive scientific information was discussed near the modified phone. Nevertheless, the Bureau suspected that the bug could have been used for industrial espionage purposes. It could have been used, in the near future, to pick up information about the U.S. monitoring of upcoming French nuclear tests in the Pacific.

Surprisingly, the FBI was informed by Assistant United States Attorney that there didn’t appear to be a “violation of interception of communications statutes” and that “no investigation [was] desired under [Interception Of Communication].” Nevertheless, the FBI’s contact at the Hawaiian Telephone Company was “discretely [sic] reviewing telephone records for possible leads.” The Bureau decided to leave the device in place for the time being in order to monitor it and discover who was exploiting it. Hills, who was an engineer, was to discreetly check it regularly.

This last point brings us to one of the more obvious reasons for leaving a listening device in place: simply determining who was behind it, either in order to arrest them (and ideally any of their compatriots) or at least to enable a real damage assessment. Simply knowing what information has gotten out does little good without an idea of who will have it, and it’s next to impossible to judge how information will be used without knowing who has it. This is one of the primary reasons for law enforcement to leave a bug in place. While counterintelligence officers would also be interested in the same information, a clever officer or group of officers would use the bug as a way of feeding the listener specific information and misinformation in order to manipulate them in various ways.

The FBI is a law enforcement entity first and foremost, despite the Bureau’s counterintelligence activities. While it didn’t neglect the latter, the former would always take precedence. FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley responded in a teletype, stating that the Bureau’s Radio Engineering Section didn’t have enough information to analyze the instrument or suggest any specific investigative techniques, though this might change when they received the pictures of the device. In the meantime, Kelley had an idea: use a voltmeter to look for “a voltage indication when the telephone is not in use” which “would indicate the device is being activated.”

The file doesn’t appear to specify what happened with the case, though a new FOIA request has been filed to learn more about the possible act of atomic espionage, and one of the new instances where FBI’s Technical Security Surveys are known to have discovered a bug. In the meantime, you can read the full memos in the embedded file below, or the rest of the files on the request page.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

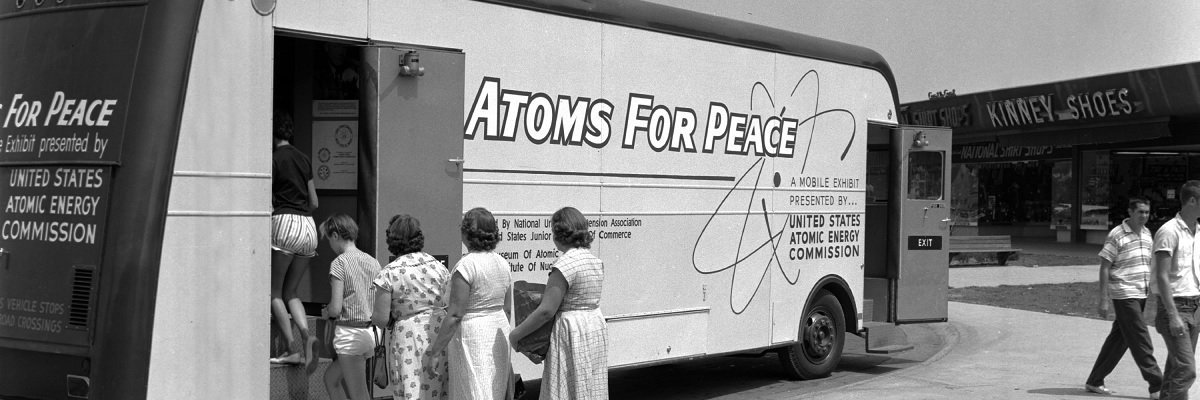

Image via Nuclear Regulatory Committee Flickr