This story, produced in collaboration with THE CITY, is part of “MISSING THEM,” THE CITY’s ongoing collaborative project to remember every New Yorker killed by COVID-19.

The city has tapped a landscaping company with no experience running cemeteries or public spaces to help transform Hart Island, the long-neglected gravesite of thousands killed by COVID, into a refuge for families and other visitors.

The management contract has both the leaders of some of New York’s largest graveyards and families of those interred on Hart Island concerned over the fate of the City Council’s $85 million vision to turn the potter’s field into the nation’s largest municipal cemetery.

Meanwhile, the city Parks Department plans to keep a former Rikers Island captain who supervised inmates carrying out emergency burials of pandemic victims in charge of interments.

“In order to restore public confidence, New York City should hire an experienced cemetarian to oversee management of Hart Island,” said Melinda Hunt, president and founder of the Hart Island Project.

Last month, the city Department of Social Services awarded a three-year, $33 million contract to JPL Industries, also known as J. Pizzirusso Landscaping Corp. The Brooklyn landscaping company’s other work for the Parks Department centers on planting street trees and roadway work.

‘Like Visiting a Prison’

The new contract coincided with a planned handoff of control of Hart Island — the gravesite of over one million New Yorkers killed by COVID, AIDS and more — from the Department of Correction to the Department of Parks and Recreation.

It was a milestone set in motion by the City Council, which in 2019 passed a law ordering the transfer. The aim: turn a largely decrepit Potter’s field dating back more than 150 years into a public, readily accessible cemetery.

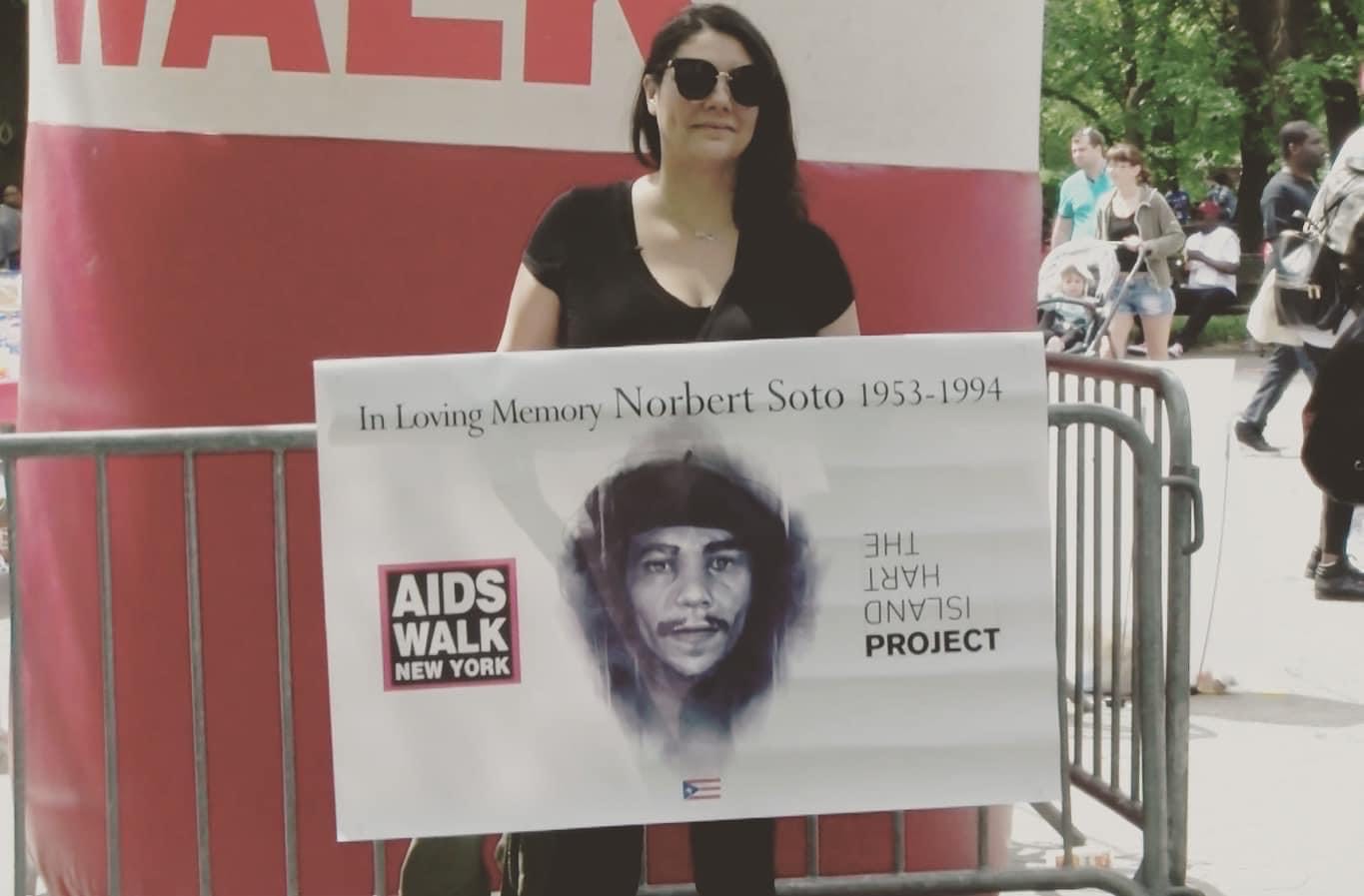

Visiting loved ones’ gravesites has proved an ordeal for people like Elsie Soto,who grew up in public housing in Lower Manhattan and now lives in The Bronx.Soto’s father, Norberto, died from AIDS-related complications in 1993 when she was 8 years old.

It took Soto and her sister 24 years to first visit her father’s gravesite. “It was very emotional,” she said. “I felt like I was visiting a prison instead of visiting my father. I was just standing in the middle of an empty field. My father wasn’t a prisoner and neither were the others buried there and they shouldn’t be treated like that.”

Elsie Soto lost her father when she was 8 years old. Courtesy of the Hart Island Project

Elsie Soto lost her father when she was 8 years old. Courtesy of the Hart Island Project

David Fleming, the legislative director of New York State Association of Cemeteries, described Hart Island as having “tremendous potential,” but requiring a “significant change” to operations to make it sustainable.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of industry partners and I’ve toured the site and a lot needs to be done to allow Hart Island to operate for a very long time, including having modern cemetery administration and technology,” Fleming said.

The first step, those who work in cemeteries say, would be hiring a company experienced in record-keeping, burying and disinterring — as well as managing large public cemeteries and dealing with visitors and family members.

‘Knowledge and Experience’’

“Indefensible” was the word City Council Speaker Corey Johnson used in 2018 to describe the extremely limited access and forbidding, jail-style visitor rules that greeted those who attempted to visit the 130-acre island.

Now, champions of a more open Hart Island say they’re concerned that too little is on track for change. In a presentation to bidders, the Department of Social Services said it sought “a qualified cemetery management and operations firm or other similarly qualified contractor.”

The agency then awarded the contract to JPL Industries. As it did on an emergency basis at the height of the pandemic, when bodies of COVID victims arrived by the truckload, JPL will continue to handle the remains of New York’s poor.

JPL Industries, contacted multiple times by phone and email, did not respond to requests for comment.

And while management has shifted to the Parks Department, the boss in charge of the burial grounds remains the same: Capt. Martin F. Thompson, a career Department of Correction officer, who has overseen Rikers Island inmates’ gravedigging work on Hart Island since 2005.

“Captain Thompson’s knowledge of and experience with Hart Island is unparalleled in New York City, developed and honed over decades of dedicated service on the Island,” Isaac McGinn, a spokesperson for the Department of Social Services, said in a statement.

But Hunt cited Thompson’s uninterrupted role as a warning sign.

“The whole point of passing legislation was to end association with the penal system. From a public relations perspective, putting the same person in charge… probably isn’t going to convince anyone that things have changed,” Hunt said.

Investing $85 Million

Roughly 1 in 10 New Yorkers who died of COVID-19 or pandemic-related causes in 2020 were ultimately buried on Hart Island, according to an analysis by Columbia University’s Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism and THE CITY based on city data. The number of burials in 2020 was more than double those logged in 2019.

Of the 3,200 people buried in 2020 and 2021 whose names and other identifying information have been made public, the median age has trended downward, from 69 in 2020 to 66 in 2021.

This summer, the Department of Buildings ordered the emergency demolition of 18 aging buildings on the island at an anticipated cost of $52 million, citing “public safety” — part of a planned $85 million in investments.

Soto last visited Hart Island last month and said it received a nice “haircut,” with mowed lawns and new benches.

But Hart Island is still tough to visit.

It’s hard to get a spot on the twice-a-month visitor ferry, or even a callback from the Department of Parks and Recreation. Only individuals with close ties to those buried there can request a visit and must sign a liability waiver. Once there, the island lacks even benches to sit on.

Operators of some of New York’s large private cemeteries declined to be quoted, but conveyed the view is relying on inexperienced contractors.

JPL Industries first worked on Hart Island at the height of the pandemic, when the Parks Department hired the company for $1.64 million on an emergency basis to bury thousands of COVID-19 victims in mass plots. Its new three-year contract includes an option to renew for another three years.

The company, with dozens of active city contracts totaling at least $60 million, lacks a website. It’s also in the midst of a $1.3 million lawsuit against the city over hundreds of tree plantings in Brooklyn neighborhoods that, the company claims, were delayed or mismanaged by city officials.

‘Selected on the Merits’

Executives from several cemetery companies invited to bid on the Hart Island contract described the process as confounding, and expressed astonishment that a landscaping company won.

One executive said there were “so many underlying variables that were unanswered” — including key questions on city staffing and future ferry service — that the company chose not to submit a bid.

Thousands of pages of bid-related documents, obtained as part of a New York Freedom of Information Law request by Columbia’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock, detail the significant amount of work projected to ensure Hart Island maintains burial capacity — and becomes an “aesthetically pleasing and welcoming environment for visitors.”

The Department of Social Services said the procurement process J. Pizzirusso won was competitive, evaluated and scored, with the contractor “selected on the merits.”

“Together, we look forward to continuing to reform the city’s end-of-life planning processes, with a continued focus on equity, inclusion, and dignity for all, regardless of background,” McGinn said.

Jail Break

Until the recent switch to Parks, burial ground operations were an offshoot of nearby Rikers Island, the city’s embattled main jails complex. Thompson, Hart Island’s newly named executive director of municipal cemetery operations, is a longtime city jail employee who started with the Department of Correction in 1988 as a guard.

Thompson has a broad mandate, according to the job description for the role: as the “chief advisor” to city leaders “on all matters related to cemetery operations at Hart Island.” At the Department of Correction last year, he made a $109,000 base salary, and $62,400 in overtime and extra pay.

But one thing has changed: Hart Island has ended its long-standing practice of using inmates to bury bodies. The Parks Department now has rangers staff the island and says it’s loosening some restrictions, now allowing visitors to take photos of grave sites.

Outgoing Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez (D-Manhattan), who introduced legislation to make Hart Island accessible to the public in 2018, said the city needs to ensure that changes are “done right.”

“Although we would like to see Hart Island become the cemetery we would have all hoped it would become as soon as possible, we need to make sure that the process to repair and transform the island is transparent, respectful and done by professionals in the field,” Rodriguez said in a statement.

This story was produced in partnership with THE CITY by Documenting COVID-19, a project of Columbia’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock.

Header image by Ron Adar/Shutterstock of ferry carrying Special Operation Medical Examiner refrigerated truck travels to Hart Island, where unclaimed bodies of COVID-19 victims were buried on April 16, 2020 in Bronx. In-article photographs provided by Elsie Soto.