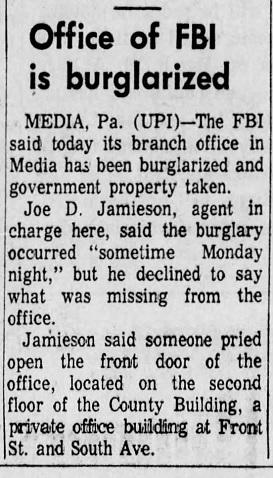

At the height of the anti-war movement, a group of seven dissidents calling themselves the “Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI” hatched a plan to reveal what they believed to be a widespread, politically-motivated domestic surveillance program run by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. On March 8th, 1971 - 48 years ago today - they broke into an FBI field office in Media, Pennsylvania and stole over 1,000 classified documents.

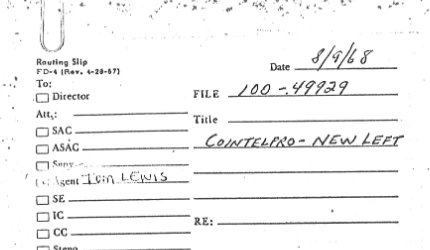

These documents led to the public exposure of the Bureau’s now-infamous domestic Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO), which, under the leadership of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, conducted widespread surveillance of American citizens and mostly left-wing political groups and activists, including civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr.

The Citizens Commission sent copies of these documents to a senator, a congressman and three newspapers. The New York Times and Los Angeles Times both alerted the FBI and deferred their publication. Only the Washington Post, under the leadership of editor Ben Bradlee, decided to publish.

The revelations in these documents, once public, ignited a national discussion about government secrecy and national security. They also helped to spur the creation of the Church Committee in 1975 and to bring about the end of COINTELPRO (although some aspects of the program continued).

The reporter who received the files and broke the story is Betty Medsger, who is also the author of The Burglary, a book detailing the Citizens Commission’s efforts to unveil the FBI’s surveillance program and how Hoover’s Bureau responded. To mark this milestone in government transparency, MuckRock spoke with Medsger about journalism’s cultural shift in the ‘70s away from blind trust in the national security apparatus, how whistleblowers helped push efforts to strengthen public records law, and the surprising incompetence of FBI investigators.

Looking back on the burglary and your reporting on it 48 years later, what do you think the impact of that story - the work you did, the work the burglars did - has been on transparency reporting?

The impact has been enormous in various ways. It’s a cumulative effect, especially in that first decade.

The first thing to realize is how secrecy was respected and assumed up until that time. One of the greatest impacts of the burglary is that what was revealed caused people to realize, including the U.S. Congress and journalists, that the FBI was something completely different than what they understood it to be. And they quickly realized that was because everything was secret. The culture at that time in Washington among journalists and government officials was that FBI and intelligence agencies should be free to keep their secrets, free to do whatever they wanted to do. But I think it’s safe to say that few people would have assumed they were using that secrecy to do something as outrageous as the cumulative crimes that were revealed eventually in COINTELPRO and other FBI files.

What I think, looking back, is that the single most important thing that happened was the strengthening of FOIA by Congress in 1974. The law had passed in 1966, but it didn’t have strong enforcement provisions and Congress had not added that. J. Edgar Hoover was probably the worst but not many leaders in government were very happy about the Freedom of Information Act in 1966, and he specifically ordered FBI officials to never provide information. I’m not even sure that reporters had asked for FBI files — it was just, again, assumed that they wouldn’t be available.

The first Freedom of Information Act request that took place successfully was when [NBC reporter] Carl Stern filed for the founding documents that would explain what COINTELPRO was. So that shows you in more ways than one how important [the burglary] was. Now, when he was filing, he didn’t even know that single-page document with COINTELPRO at the top existed until sometime a year after the burglary. And he asked for it, in a routine kind of way, and was rejected multiple times, and then he sued. And he was suing under the 1966 law. And it may be the only time that the 1966 law was used successfully to file for federal documents.

[E]ven though the law was passed, when you look into the history of its passage in ‘66 it’s sort of a miracle that it ever happened. But ‘74 was a real transition, because by the time it was strengthened in 1974, the culture was changing. More information had come out; Carl Stern had gotten those founding pages. And then he immediately turned around and he filed for actual COINTELPRO files and got them.

Other people then filed for COINTELPRO files and they started coming out. And all of that added up, and there was a subcommittee in the House that held a first hearing to discuss some of those files.

To get the content of what they would discuss at that hearing, the Justice Department went along with an FBI ultimatum that they wouldn’t even show the Justice Department, which were their bosses, the file. And instead, the FBI would write summaries. Well, the summaries, as it turned out, were not a reflection at all of how serious the documents were. So again, the pressure was building to get original documents out. And the action in strengthening FOIA in ‘74 was absolutely crucial.

Another crucial development happens after, at the end of December 1974, when [New York Times reporter] Sy Hersh writes the explosive story about the fact that the CIA, in violation of its charter, had a massive domestic surveillance operation going on. That was the CIA equivalent in power to the Media files. But you can see how it took time for all of these things to develop. In April, one month after the first story on the [Media] files, Congress refused to conduct an investigation. And then, by just weeks after the CIA revelation at the end of 74, in January of ‘75, both houses of Congress decided to investigate. And then we have the maximum exposure: an extensive investigation by the staff and then public hearings that were quite dramatic.

Do you think those investigations maybe wouldn’t have happened without the burglars’ whistleblowing in 1971? The Pentagon Papers, as well - it seems like that may have also been important for the cultural perspective on transparency.

Oh yes, the Pentagon Papers. There are all these steps that take place, each one of which is essential. And the Pentagon Papers came three months after the Media files, and it turns out that Ellsberg was watching what happened with the Media files and had deep regret that his name became attached to [the Pentagon Papers] so quickly, because the focus switched to him the subject as opposed to the substance of the documents. To this day, he feels that lessened the impact of the papers themselves. But the truth is that what people really remembered was massive lying to the public about war from the beginning. And so that was a huge impact also in saying, the military and intelligence agencies have gotten a free ride and beginning in that spring there was the development of a new culture: instead of secrecy, a culture of accountability even for those parts of government.

I think, in fairness, that the change in this culture actually started - but not in a way that spread into other agencies - with the military during the [Vietnam] War. I mean, the access that journalists had, and that journalists like [New York Times reporter David] Halberstam used, was unprecedented. The same attitude existed there, probably even more strongly, that the military had to be free to do whatever it wanted. And because of the kinds of questions that Halberstam and others started asking about the war, and included in their coverage - plus the good TV coverage - again the public started to be aware that accountability needed to expand to these agencies that were sacred.

I’ve been thinking lately about how it’s often the case that there is a certain social or cultural readiness to inspire and provide a big and eager audience for certain types of reporting. It seems the same may be true of transparency work around national security issues, because the public was so trusting before.

With the Media burglary, did you feel like you found yourself at the center of a cultural watershed moment that was happening in the early ’70s, and how did that influence the rest of your career and what you wanted to do as a journalist?

I’d like to go back to your term, cultural readiness. That is a really good term. Some information could come out and it would be ignored, essentially, like a quick-cut story but with no desire to take action about it. In all honesty, I’ll have to say that at the time, I didn’t have the feeling “Wow, these stories are going to make dramatic change and they are crucial to a movement that’s going to take place.”

An important thing about me at the time is that I was so young and new to Washington. I also didn’t know what happened at the other two newspapers until I was doing the research for my book. What happened at those other two newspapers - there were two very dramatic things and different from each other - but what the New York Times did, looking at the files and turning them in and never even thinking about writing about them until we published our story the next day, that more than anything illustrates this culture of the time. It was just a natural thing to do. A couple editors and the person who covered the Justice Department, who was widely respected, it just didn’t even occur to them that you should write this story.

Well, there I was, and I wasn’t part of the culture of Washington reporters, I had been there too short a period of time. So to me, I just said, “My God, this is significant, this is important, the public needs to know this.” If I had been more seasoned, I would have just assumed it was my job to suppress it, I think. I probably wouldn’t even have used a strong word like that, it would’ve just been, “Oh, this is not something you deal with.”

To what extent do you think the burglary story helped instill that ethos in a new generation of reporters?

Well, when you look back on it, it’s clear that it was an important block in what got built as a new approach to journalism. But it certainly isn’t what people remember as the cause in the change in journalism. It’s just inevitable that the unfolding Watergate coverage that led to the resignation of a president, that’s what will always appropriately be remembered.

But an important part of that movement, it seems like.

Oh, yeah. Definitely. I didn’t fully grasp all of that until I was working on the book, and I definitely didn’t know the impact I was having inside the FBI until I read the 34,000 pages. The day I wrote a story that quotes from files that were in the packet that contained the COINTELPRO revelations, I described in the book, Hoover himself plus other high officials just went berserk at that point. Because they knew that, if I had what I had reported on, I also had that cover letter, the memo that had the term COINTELPRO on it, and that led to a lot of activity.

Can you talk about what you found about the FBI and their discussions of you and the story while doing research for the book?

I discovered it while reading the 34,000 page FBI investigation on the burglary. Which is now at Swarthmore’s Peace Collection.

Is there anything you found that really surprised you?

It happened repeatedly. I suppose the biggest surprise, even for me, was to see the incompetence at work. The way they went about the investigation: “We’re going to look at all people within so many miles who have long hair and look like hippies.” I mean, really, please. In 1971, after all the draft break-ins that occurred, that’s what you think is the angle?

I remember talking to John and Bonnie Raines [two of the burglars] about the FBI visiting their house and then leaving after a few questions about the burglary. John said he wouldn’t even flat out say he wasn’t a burglar; he just refused to talk.

Well, that visit to the Raines’ house that day was pretty traumatic in terms of what almost happened. Bonnie came home five minutes after they left, and they were all carrying around the likeness of her. If she had arrived it may have been a crucial moment. But what is amazing is how John treated them, and then, here’s one of the moments when I’m reading along in the files and I discover that two weeks after they visited him and all of that strange behavior took place, they removed him from the list of suspects. That’s the kind of thing that would happen repeatedly in the documents.

Public Records Reporting and FOIA has become a lot more systematized, and a lot more important to reporters since the early ’70s. Is it still important to have leakers, whistleblowers and the like in an age where there is a much stronger bent toward transparency work through legal public records avenues?

That’s a good question, because it was so different. It seems as though everything is sealed in such a tight circle now. A reporter walks into the State Department front door, they have a badge with a chip that informs them the person is now there. They call someone in the State Department, that call is monitored. It seems as though, how could a government source be of value to anyone without getting caught?

But it seems to me that [Edward] Snowden is the evidence that it’s still extremely important. The morning that I read the first story [on the NSA], it was less than a year before my book would be published and so I was finishing up the final writing. And I was just amazed and thinking “Ok, here we go again.’ And as I learned more about his thinking, he had almost precisely the same rationale ethically and as far as what his goal was for the public as the burglars or Ellsberg. And there’s just so much we either can’t get access to or that’s made very difficult to get access to, and so I think whistleblowers are still very important. But I think it’s a much greater challenge to do something like burglarize an FBI office now. You couldn’t trick the technology and get in the way you could then.

It is important to talk about the power of the technology to close a door, to create many more files but to make things less accessible. It’s very important to realize that. But at the same time, the huge difference is that there is an active culture among journalists now that is a constant. Some people do only that kind of work, where they’re filing on a constant basis. But it’s also very difficult and costly sometimes to do this.

Is there anything you want to add I didn’t ask about?

I guess one of the things that sometimes gets lost is the burglars themselves. Here were eight people who were willing to risk their freedom for decades because of their belief that, first of all, people’s rights were being suppressed and they did not know. But that if they knew, through documentary evidence, that the FBI was doing this, they would care, and despite their adulation of Hoover all those previous years, they would eventually demand that this be stopped.

I think we talk about resistance rather lightly these days. But these people, to a person, believed in that ideal so firmly that they were willing to sacrifice their lives for it.

Metsger photo via C-SPAN

Header image by smallbones via Wikimedia Commons