An additional 57 pages of Federal Bureau of Investigation documents shed more light on the FBI’s 1976 investigation into The Village Voice and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press regarding the publication of the classified and censored Pike Committee report. The documents also reveal details of how the Bureau approaches espionage investigations of news outlets and journalism organizations.

An additional 57 pages of Federal Bureau of Investigation documents shed more light on the FBI’s 1976 investigation into The Village Voice and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press regarding the publication of the classified and censored Pike Committee report. These files contain official confirmation that the Bureau’s investigation include the RCFP, a fact that was previously improperly redacted. The documents also reveal details of how the FBI approaches espionage investigations of news outlets and journalism organizations.

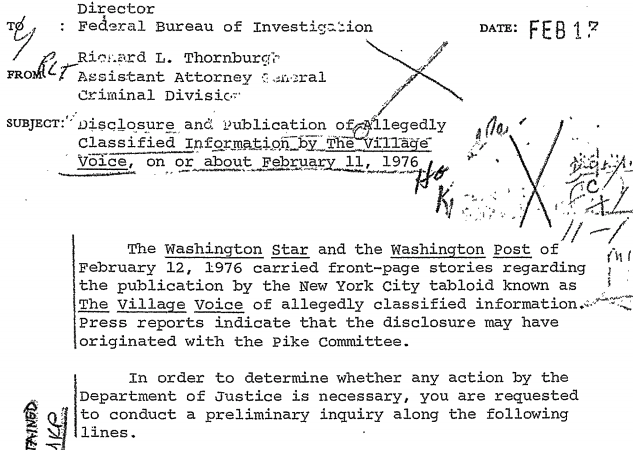

The Bureau’s investigation began as many of their other inquiries about unauthorized disclosures do – with the “11 questions.” Covering the specifics of the disclosure, whether the information was accurate, where it came from, what had been officially released, if a declassification decision had been made and what the consequences of the exposure could be.

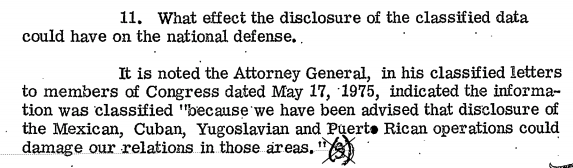

The answers to the “11 questions” universally held that the information had been properly classified and that the disclosure had been unauthorized. The government’s case, however, was undercut by the fact that the sole argument they could make for harm resulting from the disclosures was they could damage relations with the countries and territories they affected. In other words, the “damage to national security” was not only limited to but synonymous with accountability.

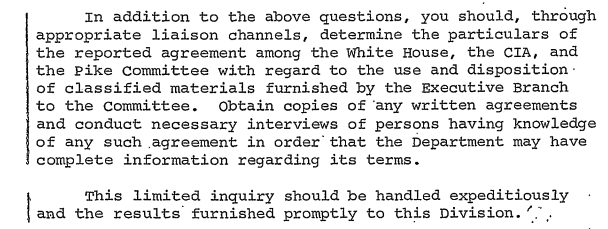

A letter from Assistant Attorney General Richard “Dick” Thornburgh to FBI Director Clarence Kelley also carried instructions to look into the information sharing and non-disclosure agreements between the Central Intelligence Agency, the White House, and the Pike Committee. This set of inquiries would include obtaining copies of any agreements and interviewing those with knowledge of them. The result of the Bureau’s inquiry were to be “furnished promptly” to the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice. Kelley soon relayed these instructions to the Bureau’s New York field office.

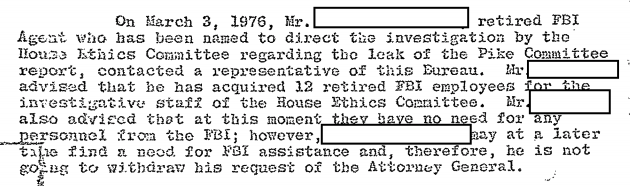

The parallel investigation, previously discussed by MuckRock, was carried out independently. The House Ethics Committee’s investigative staff was filled by a dozen retired FBI agents. While the Committee was ready to call on the Bureau for assistance, they maintained relative independence when it came to the personnel involved. The FBI noted that the broad strokes of these facts were reported by the United Press International virtually in real-time.

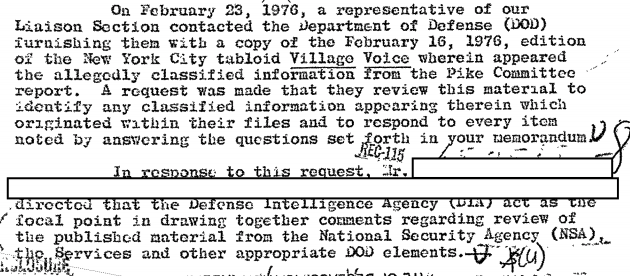

Mirroring a pattern that would firmly enter the public consciousness in the wake of Chelsea Manning’s and Edward Snowden’s disclosures, an information review task force was created. While this incarnation appears to have been less formal (and wide ranging) than its more infamous successors, nevertheless, it involved many of the same individuals. The Defense and Justice Departments coordinated their reviews, involving the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, the National Security Council, the Department of State’s Intelligence Liaison, the CIA and various other elements of the DoD.

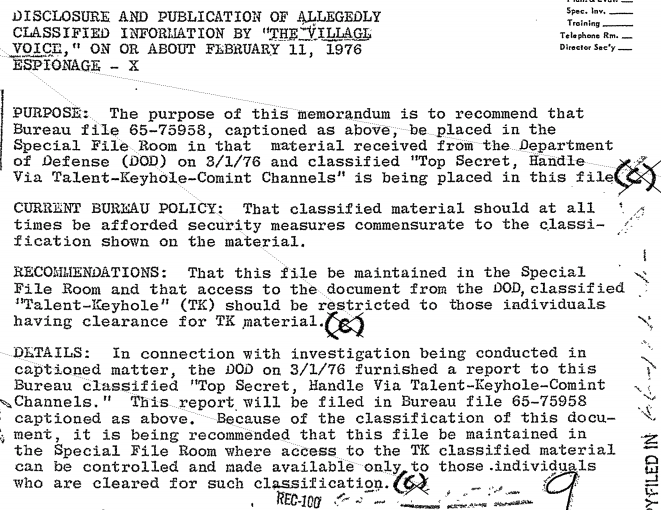

This review resulted in a report that was highly classified and compartmentalized, resulting in it being limited to viewings in SCIFs (sensitive compartmented information facilities) and transmittal through TALENT-KEYHOLE-COMINT channels.

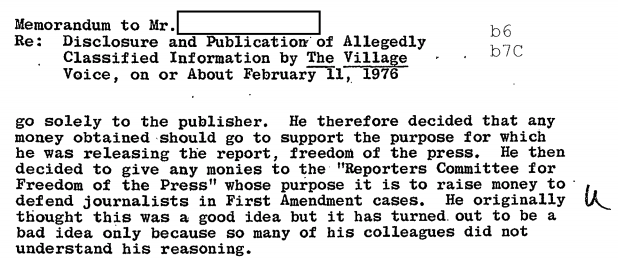

A significant piece of the FBI’s investigation comes from a “Behind the Lines” interview on aired on WETA. As MuckRock previously discussed, much of the Bureau’s focus was on the apparent transfer of money relating to the publication of the Pike Committee report. According to the interview, the donation to the RCFP wasn’t a reward for helping Daniel Schorr find an outlet for the report, but simply a way to prevent the publisher from receiving additional money as a result of Schorr waiving his royalties. As the FBI had separately learned, this had been a divisive and apparently misunderstood element of the affair.

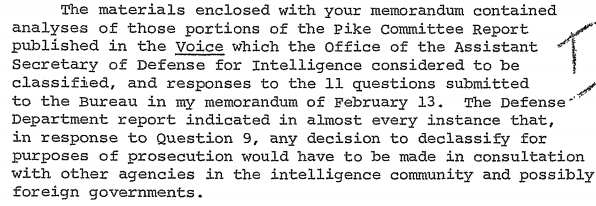

A report of Thornbrugh to Kelley notes that the DoD felt that the decision to declassify the information in order to allow prosecution could only be made, in some instances, after consultation not only with other government agencies, but potentially with foreign governments as well. In context, this fact is not surprising. Its official acknowledgment, however, is noteworthy.

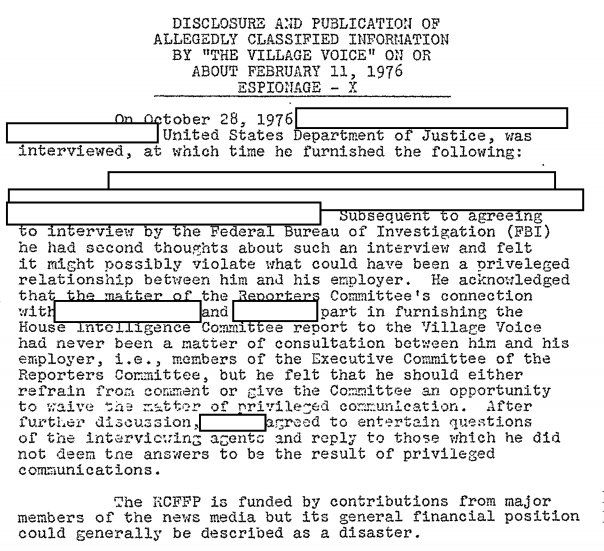

This set of files contains one of the Bureau’s summaries of the case, dated November 3rd 1976. Unlike other versions of the file, this copy doesn’t redact the RCFP’s identity.

The summary also reveals the Bureau spoke to someone from the RCFP. The individual repeatedly said he didn’t know specific details about various aspects of the case, and actively declined to comment on any connections to The Voice or details of any financial consideration relating to the Pike Committee report. A second interview, presumably with another individual, was conducted the following day. It was similarly unable to provide the key details the Bureau was after.

Read the latest batch of documents below, or find more on the request page.

Image by Underdestruction via Flickr and is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0