Imagine that you send intimate photos to your significant other. After a difficult breakup, your private images end up online and emailed to people that you know.

Now imagine that you took topless photos of yourself and emailed them to your personal computer. They suddenly appear on an image sharing website, despite the fact that you never sent them to anyone. You find out that a stranger hacked your online accounts, then published the pictures online.

These are realities for victims of nonconsensual pornography.

Nonconsensual pornography, also known as revenge porn, is the distribution of pornographic images without the consent of the individuals pictured. Despite its name, revenge porn does not always have a vengeful motive behind it. Publishers of revenge porn will often post nonconsensual images simply to make money or to brag about “sexual conquests.”

Regardless of the intent, NCP can have devastating effects on victims’ lives. Victims of NCP have reported experiencing PTSD and depression, job loss, and stalking.

According to a 2017 study by the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative, around one in eight adults in the U.S. have been victims of, or threatened with, NCP. Despite high profile cases such as the 2014 “Fappening” and the 2017 Marines United scandal, there are still no federal laws prohibiting NCP. The main issue with passing a federal law has been striking a balance between First Amendment rights and rights to privacy. NCP is criminalized in 40 states and Washington, D.C.

- Blue = NCP law

- White = No NCP law

However, there are discrepancies between each state’s classification and punishment of the crime. Some states categorize the crime as a misdemeanor, and others categorize it as a felony. Each statute has its individual qualifications and exceptions to the individual laws. These factors affect the strength of a state’s law, and whether they are effective or not.

In states without NCP laws, victims can seek justice through different means. Depending on the methods used to collect and distribute the images, perpetrators of NCP can be charged with extortion, child pornography, unlawful surveillance, or hacking. Additionally, some victims may try to take their abusers to civil court for emotional distress or copyright violations (if the victim copyrighted the images they took). However, civil lawsuit can be prohibitively expensive, and lead to unwanted public scrutiny.

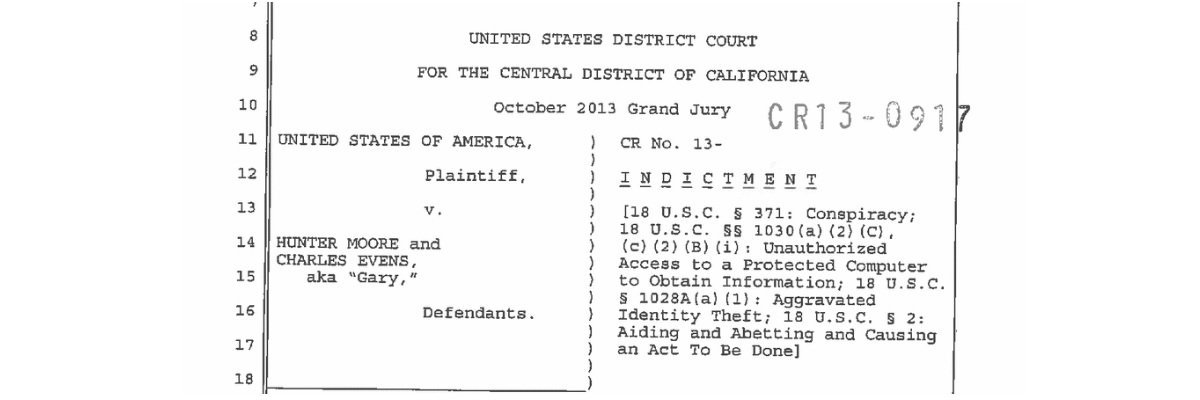

A few years ago, MuckRock reported on the FBI’s investigation into Hunter Moore’s now-defunct revenge pornography website, Is Anyone Up? Moore’s former site hosted stolen or leaked pornographic images of unknowing victims. Moore was later indicted for the methods he used to obtain the images, not for any sex crimes. NCP was not a crime in most places in the early 2010s when Moore’s website was at its peak. At the time of the investigation, state legislation on the topic was only beginning to be enacted.

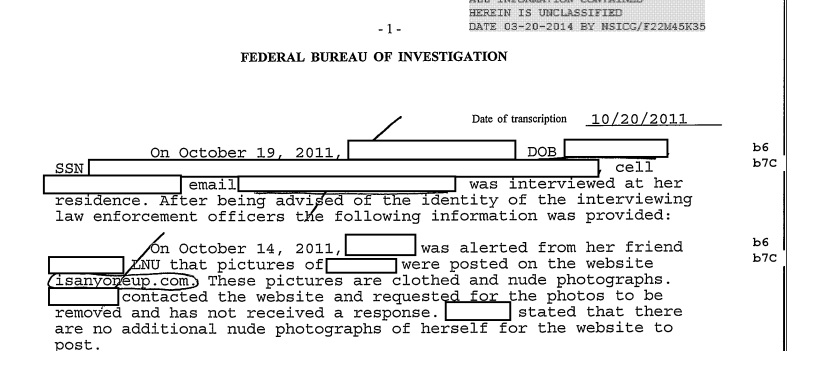

Moore and an associate, Charles Evens, were each sentenced to two years in prison in 2015. The two men had been charged with identity theft and unauthorized access to online accounts after hacking into several victims’ email accounts and stealing their nude photos. The FBI file obtained by MuckRock in 2014, although heavily redacted, gives some insight into how the bureau investigates revenge porn cases. The investigation mainly focused on whether the pornographic images were stolen. Evens and Moore were indicted because they illegally obtained the nude images and published the stolen content.

Unauthorized hacking and identity theft are serious federal crimes, but as Moore said himself, he is not liable for the user-submitted revenge porn hosted on his website. Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, website providers like Moore are not viewed under the law as the publishers of obscene content like revenge porn. Is Anyone Up? cannot be held responsible for the actions of its users, just like Facebook is not liable for controversial posts and comments made by its users. This is because the original content was published by an individual with distinct ideas that are not necessarily those of the website operator, who just provides the platform. Although Section 230 has been celebrated by free speech advocates, critics have argued that it has enabled internet service providers to allow obscene or illegal content on their site with virtually no accountability.

However, the passing of SESTA/FOSTA of this past March signaled to internet service providers that they may no longer to be able to ignore sinister activity on their sites. The law was intended to make it easier for victims of human trafficking to seek justice. Critics, though, believe that it will chill free speech on the internet since it weakens Section 230. Free speech is an issue that has also been at the center of the revenge porn legislation debate. Representative Jackie Speier (D-CA) introduced the Intimate Privacy Protection Act in 2016, but it was criticized for impeding on First Amendment rights. The bill never moved through the House or Senate.

Most recently, Senator Kamala Harris (D-CA) proposed the Ending Nonconsensual Online User Graphic Harassment (ENOUGH) Act in 2017, but it has yet to move through Congress. It is slightly more narrow than Speier’s bill; there are more defined first amendment exceptions, and intent to harm would have to be proved. The bill would make the nonconsensual distribution of sexually explicit images a crime punishable by up to five years in prison or an undetermined fine.

MuckRock will continue to track the status of ENOUGH Act. If you have been affected by nonconsensual pornography or would like us to look into your state’s NCP laws, tell us by contributing to our assignment below or on the Exploring America’s Nonconsensual Pornography Laws project page.

Read Moore’s file embedded below, or on the request page.