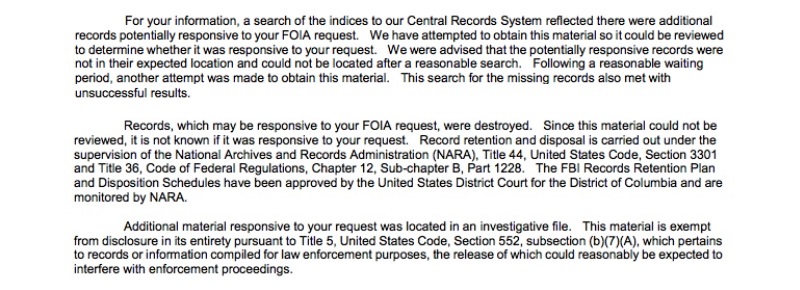

In response to a FOIA request filed January 1st, 2016, the Federal Bureau of Investigation eventually released 292 pages regarding the PROMIS scandal, the Bank of Credit and Commerce International, and the mysterious death of Danny Casolaro, while withholding or referring 101 other pages. The Bureau noted that some files were missing, others were destroyed, and some were part of an open investigative file and thus exempt under b(7)a. Following an appeal over the Bureau’s response, the Justice Department said that b(7)a no longer applied and the FBI subsequently released ten new pages. FOIA lawyers and experts are divided on whether the DOJ’s letter implies the Bureau improperly cited the b(7)a exemption, or whether it had stopped being applicable between the initial FOIA response and the appeal.

The contradictions in the FBI’s and DOJ’s responses are merely the latest in a series of inconsistencies relating to the Casolaro and PROMIS cases. In addition to the b(7)a reversal, the DOJ asserted that the FBI had not yet completed its search for files relating to the FOIA - an assertion that seems to contradict the FBI’s own letter. In the FBI’s letter, they noted only that files were missing and several attempts to locate them were unsuccessful, and that some were being referred to the DOJ’s Criminal Division and would presumably be released later.

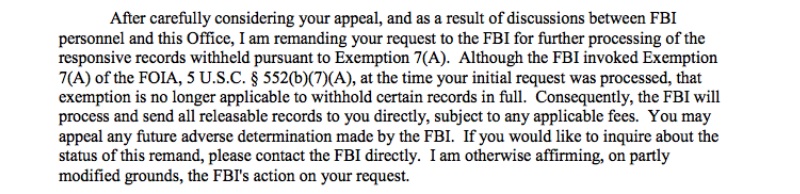

The DOJ’s language responding to the b(7)a exemption is similarly murky. “Although the FBI invoked Exemption 7(A) of the FOIA, 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(7)(A), at the time your initial request was processed, that exemption is no longer applicable to withhold certain records in full.” National security attorney and FOIA expert Mark Zaid said it “probably” means the exemption applied when the FBI cited it, but no longer did. While Ryan Shapiro, a researcher and frequent litigant, and noted FOIA reporter Jason Leopold didn’t. Given the ambiguity of the language in the Bureau’s subsequent release letter, they were asked to clarify. The FBI did not respond.

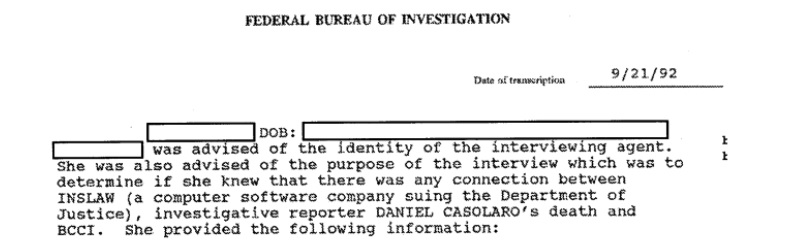

The ten pages which were released are unremarkable in and of themselves. Six pages are previously obtained versions of Casolaro’s book proposal and outline, with another four recounting a pair of interviews with individuals whose names are redacted. The first interview took place a day after the FBI falsely told Congress they hadn’t looked into and weren’t looking into Casolaro’s death. Both interviews were addressing possible connections between Inslaw, BCCI, and Casolaro’s death.

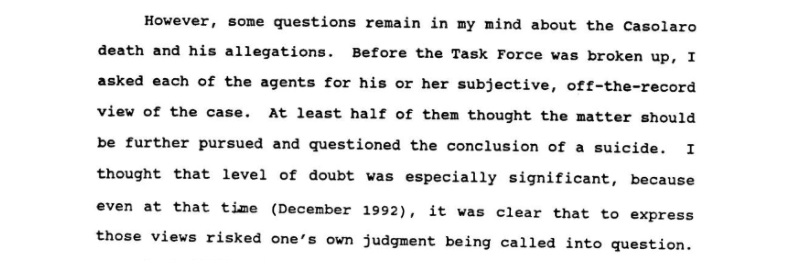

This interview would have been conducted by the BCCI Task Force, which at that time was looking into those very connections. Near the end of their work, at least half the Task Force reported doubting the conclusion that Casolaro had committed suicide and thought the matter should be pursued - despite feeling pressure to close the case. For the FBI to cite, and the DOJ to agree it applied at the time, a pending law enforcement proceeding for the case decades later would indicate that the matter remained open for the FBI long after the DOJ publicly declared the case closed.

Given the ambiguity of the situation and the FBI’s failure to respond to a request to clarify, there are alternative explanations. For instance, the DOJ’s letter could be read as saying that the FBI acted improperly and shouldn’t have cited b(7)a at all. The FBI might also have performed another search after being contacted by DOJ regarding the appeal, retroactively declaring they hadn’t finished looking. If so, this only rehighlights the Bureau’s pattern of incompetence and inadequacy when it comes to FOIA searches. Finally, the Bureau might have simply cited the entire file as exempt without looking at the actual pages. In this case, it would mean the Bureau had failed to attempt to segregate the material as the law requires.

In other words, every explanation except the investigation remaining open until 2017 involves the FBI acting improperly or incompetently.

The file seems to show that the second interview provided a handful of leads, including the name of one of Casolaro’s suspected sources and a promise to be provided with a copy of his manuscript notes. While the interview subject felt Casolaro probably had committed suicide, she also reported the autopsy showing “peculiar markings on his body which she felt were attributable to foul play.”

The first interview, presumably conducted with William and Nancy Hamilton of Inslaw, was declared fruitless by the FBI, along with their attempt to locate Danny’s sources and notes. The only lead the Bureau obtained from this interview was the name of a CNBC reporter who had apparently told them that Danny had told her First American Bank “filtered PROMIS money,” as the FBI paraphrased. William Hamilton confirmed that they were interviewed by at least one FBI agent regarding the Inslaw, Casolaro and BCCI case but was not able to recall the date.

While the release itself sheds only a few new details on the investigation, the story of its release raises the question of whether the FBI never fully agreed with the DOJ’s public conclusions, and kept the investigation open, or if the FBI’s handling of the FOIA request was improper or inadequate in some way. A week after it was sent, the FBI has failed to acknowledge the request for clarification.

You can read the FBI’s final response letter (which uses its own ambiguous language), along with the release, below.

Image via People of the Black Circle