While the 25-year declassification review program hasn’t reached the new millennium yet, contemporary public records still provide some insight into the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) efforts to audit the Intelligence Community in general and CIA in particular. After its creation and taking on some of the duties that had previously laid with Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) would pay lip service to the GAO and seem to cooperate on some issues. At the same time, it manifested the same problems, ignoring its own guidance and, like the Agency, claim that almost anything was protected as an intelligence source or method.

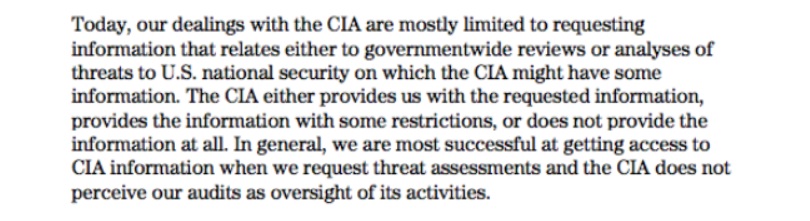

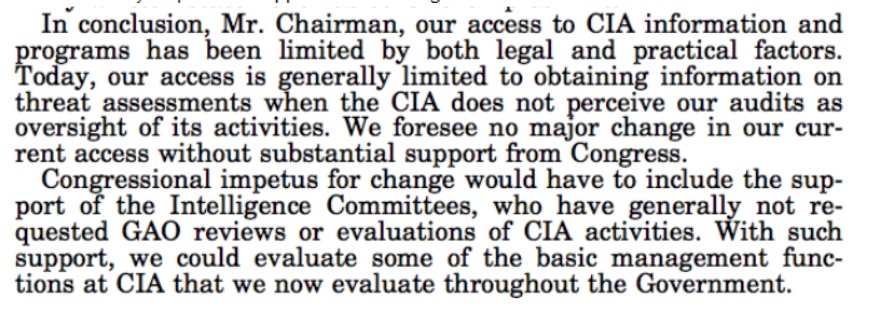

By July of 2001, the GAO’s access to CIA was unreliable at best. While the GAO had “broad legal authority to evaluate CIA programs,” they had long since given up on attempting to audit the Agency as they lacked the proper Congressional support or the ability to compel CIA to cooperate. Instead, the GAO limited their requests to governmentwide reviews or analysis. According to testimony before Congress, the Agency’s responses to these requests depending entirely on how they viewed it. If the Agency perceived the request as purely part of a threat assessment, they were fairly likely to comply. If the Agency saw the request as oversight of their activities, however, the chances of the Agency cooperating went down considerably.

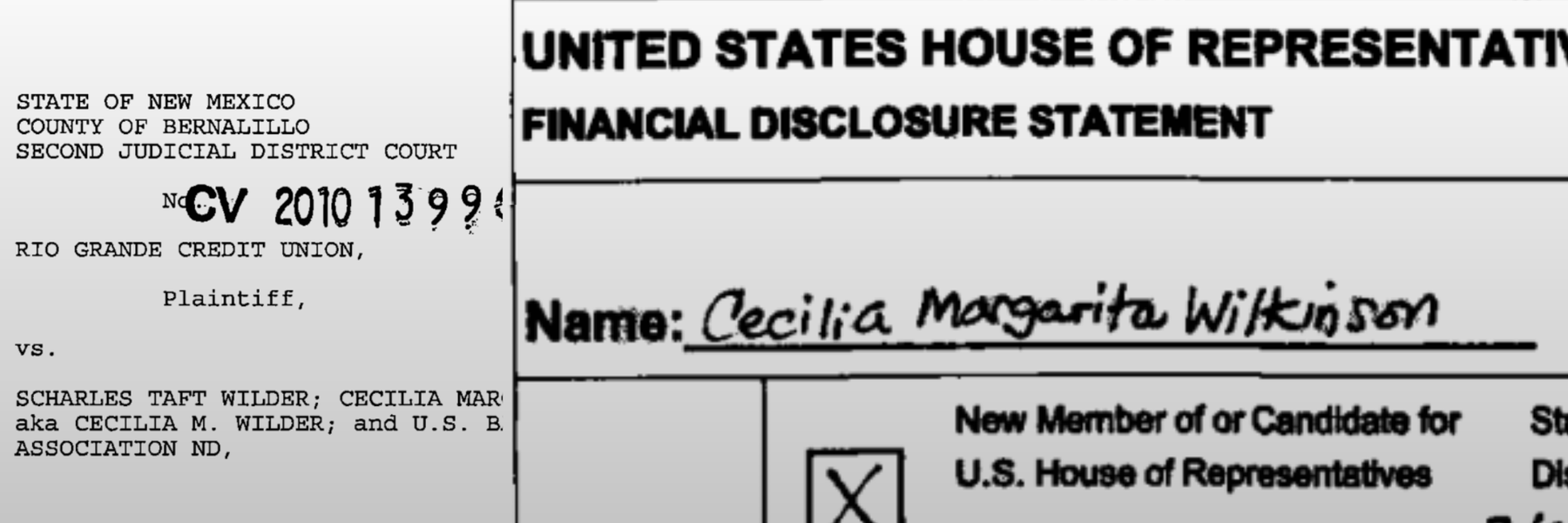

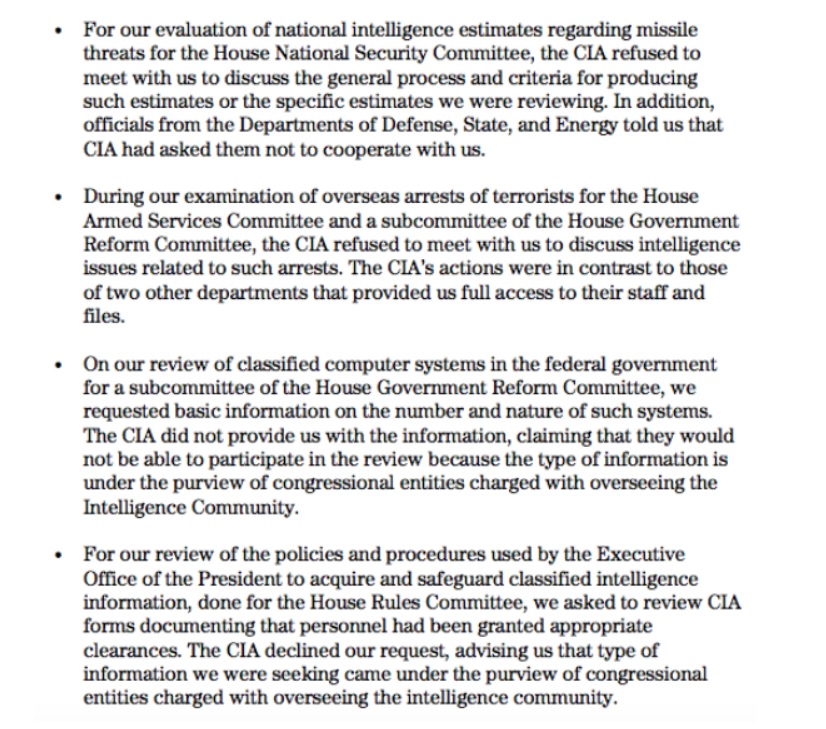

In the cases where the Agency would simply deny the GAO access to information, testimony made it clear that “the CIA’s refusals are not related to the classification level of the material.” According to the written statement provided in 2001, the Agency’s obstruction had extended as far as encouraging other agencies to not cooperate with some of the GAO’s Congressionally requested inquiries.

The above statement was produced as part of a Congressional hearing appropriately titled “Is the CIA’s Refusal to Cooperate with Congressional Inquiries a Threat to Effective Oversight of the Operations of the Federal Government?”

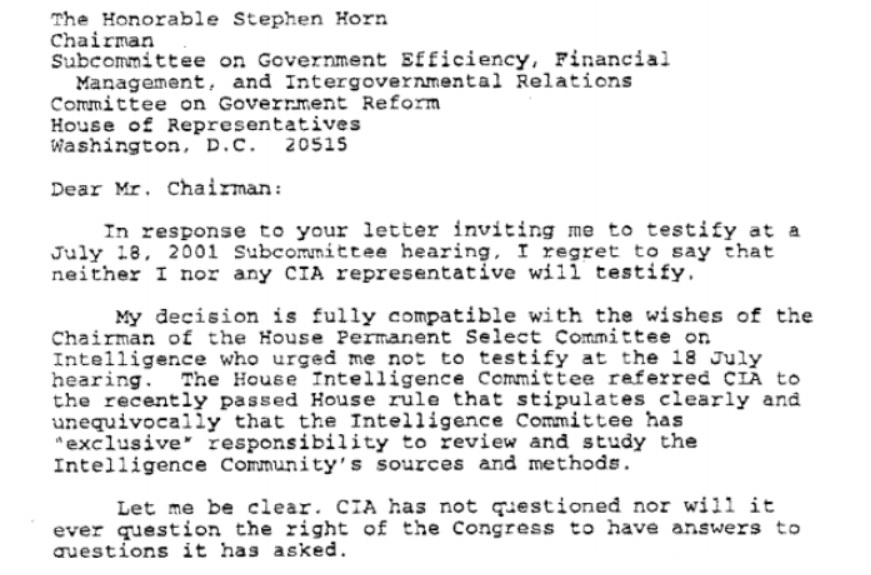

The Agency’s reaction to the hearing not only underscored its necessity but that the answer to the central question of the hearings was emphatically “yes.” As noted by Congressman Christopher Shays (R-CT), the chairman of the National Security, Veterans Affairs and International Relations Subcommittee, the Agency’s obstruction went as far as refusing to provide a witness for the Congressional hearing on CIA’s refusal to cooperate with Congressional inquiries and other forms of oversight. The letter informing the Chairman that the Agency would not cooperate with the hearing or send anyone to testify is dated the day before the hearing.

Shays also criticized the Agency’s policies regarding the GAO, calling CIA’s hard line approach a “dated [and] distorted concept of oversight.” Shays argued that the Agency’s position “is not supported by the law, is not supported by House Rules and is not supported by sound public policy.” According to the Congressman, the Agency had displayed unacceptable “persistent, institutionalized” resistance to Congressional and GAO inquiries.

While no one from the Agency was willing to come and testify, former CIA Director Woolsey did appear and give testimony. Woolsey argued that the Agency complied with oversight requests all the time, and there was no shortage of people involved in oversight of the Agency. Woolsey presented a series of numbers that argued that about 50% of Congress was involved in overseeing the Agency, for a total of 760 people (which Woolsey noted would be higher if GAO was allowed to audit the Agency). Woolsey’s argument, and his numbers, however, both fall flat.

First, few (if any) of the staffers Woolsey cited worked on CIA oversight full time. If they did, it still resulted in approximately 760 people from Congress being responsible for overseeing a highly secretive, highly compartmentalized organization with approximately 17,000 employees, not counting contractors, assets or anyone working for a CIA funded program/project. An organization whose one-time director of liaising with Congress was later convicted of lying to Congress.

Second, among one of the committees Woolsey counted as having effective oversight of CIA was one of the committees holding the hearing that the Agency refused to cooperate with.

Third, it was the Agency’s position that those Committees didn’t have jurisdiction, and that only the Intelligence Committees did. This basic argument had long been used by the Agency to prevent GAO audits. Now the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) pointed to a new House rule which CIA used to further justify their stance of non-compliance with Congressional committees, a position with which Members of Congress did not agree. The DCI added that “CIA has not questioned nor will it ever question the right of Congress to have answers to questions to has asked” - CIA simply wasn’t going to send anyone to answer the questions, that’s all.

While CIA’s legal analysis and position was rejected by both Members of Congress and the GAO, there was agreement that effectively giving the GAO authority to review CIA’s activities would effectively require the support of the Intelligence Committees.

While the Intelligence Committees were reluctant to support the expansion of oversight to the GAO or other Congressional committees, which the Intelligence Committees had come to see as competitors rather than collaborators, they were far from suited to handle oversight of the Intelligence Community as a whole or even CIA by itself. Where the GAO had what CIA called “armies of auditors”, the Senate Intelligence Committee had only three.

A theory which would be put forward by the Intelligence Committees was that the GAO was subject to political influence due to responding to Congress as a whole. The argument was that Intelligence Committees could be better trusted not to act unilaterally or politically. This theory was proven wrong in 2005 when Senator Pat Roberts (R-KS), the chairman of the Senate committee, fired six Senate Intelligence Committee staffers, apparently unilaterally and without warning. The six staffers fired included all three members of the audit staff.

The move alarmed Democrats, who viewed the firings as a move by the Republicans to eliminate “an investigative part of the committee they couldn’t control.” Lest anyone assume that the Democrats were defending Democratic staffers in their own partisan bid, Don Stone, who was the head of the audit staff until his dismissal, was a Republican staffer and well regarded as an independent and objective investigator. Nevertheless, it was the Chairman’s prerogative and there was nothing the Democrats could do to block what they saw as a bid for control over objectivity by replacing staff members. Nevertheless, the Senate Intelligence Committee did not restore the GAO’s authority to audit or review the Agency.

Read Part 2 here

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via CIA’s Flickr