Read Part 1 here

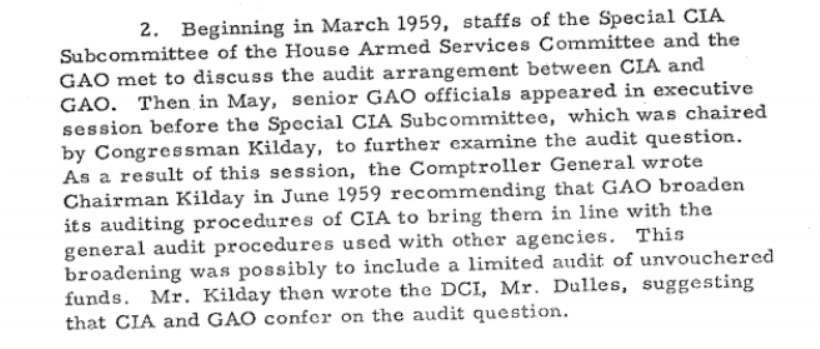

CIA’s eagerness to rid themselves of the GAO was revealed in 1960, when CIA Director Allen Dulles appears to have provided the President with inaccurate numbers about the Agency’s activities and how much was available for GAO to audit. The Agency had first been approached about the matter by the Special CIA Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, which asked the CIA to consider an expanded audit, and to coordinate the matter with the GAO.

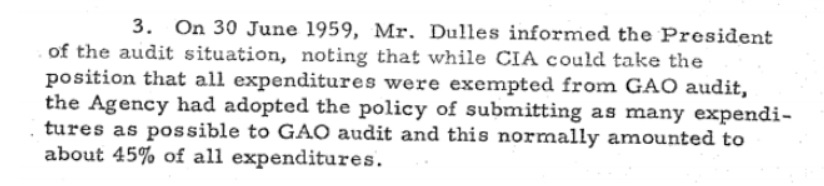

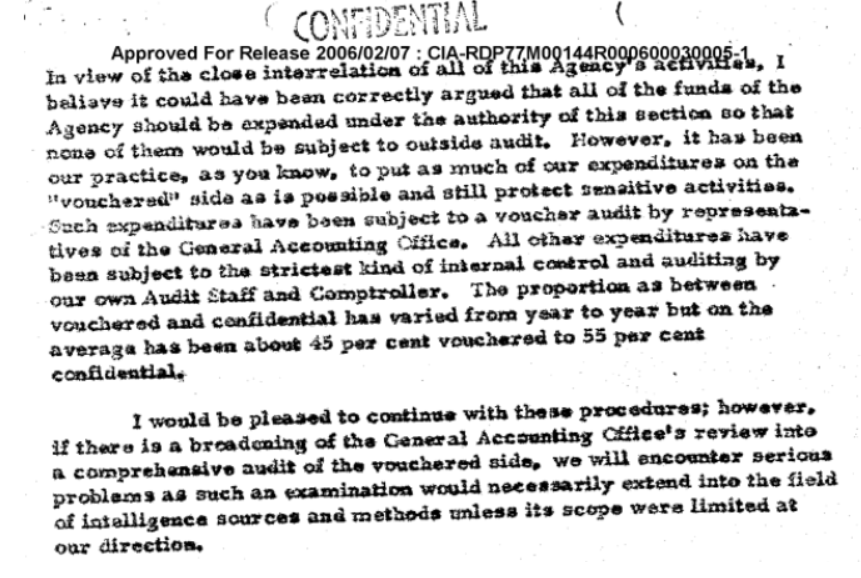

According to CIA’s previously CONFIDENTIAL Historical Review of Audit of CIA Expenditures by the General Accounting Office, the next action was taken by Dulles was at the end of June, 1959 when he wrote the President. According to the Director’s letter, CIA submitted “as many expenditures as possible to GAO audit, and this normally amounted to about 45% of all expenditures.” This number, however, is contradicted by CIA’s own correspondence with the GAO.

While the Director admitted that the proportion “varied from year to year”, he told the President in writing that it averages to about 45%. According to the Director, it was not a matter of simply vouchered versus unvouchered expenses, but one of sources and methods that needed protecting - a claim which GAO rejected as not having a legal basis for denying them access.. The Director told the President that comprehensive audit of even their vouchered expenses would be problematic “unless [the audit’s] scope were limited at our direction [sic].”

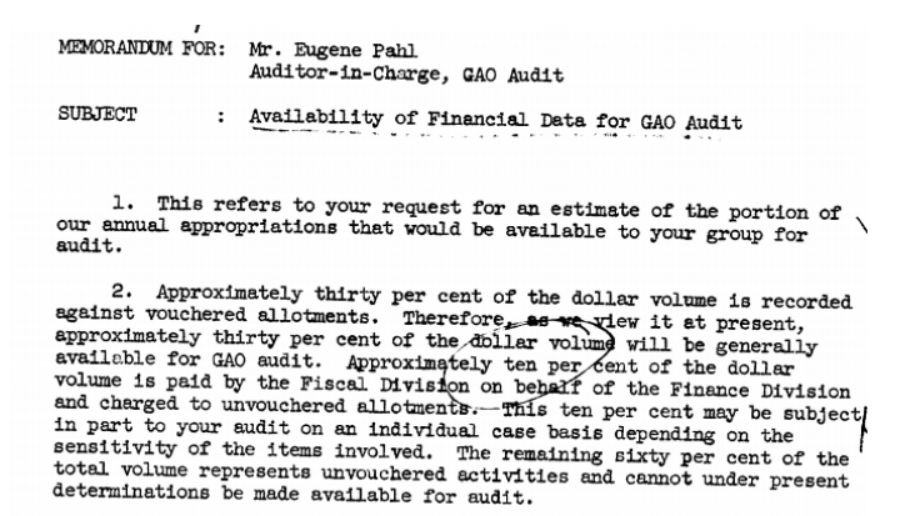

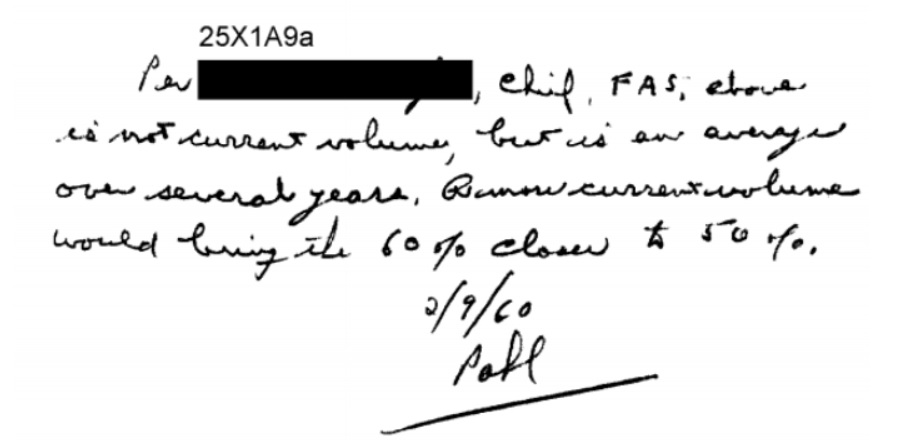

Even the “average” that the Director provided the President with, however, appear to have been an inflated number. Seven months later, the Agency’s Deputy Comptroller informed the GAO’s Auditor-in-Charge that only 30% of the Agency’s expenditures would be available for GAO audit, with an additional 10% potentially eligible for review at the Agency’s discretion and a full 60% remaining categorically unavailable to the GAO.

As noted in the margins a week later, these numbers were not current but rather “an average over several years” - completely undermining what the CIA Director had presented to the President in writing only months before. According to the numbers CIA provided to GAO, the estimate given to the President may have exaggerated what the Agency made available for review by up to 50%.

This inconsistency is a red flag in the CIA’s archives, one that is hardly reassured by the fact that the Agency refuses to release the letters where GAO detailed CIA’s obstruction of their audits.

Thanks to the reference sheet attached to the document, we know exactly which letters are redacted under 25X1:

Revealing who the correspondence was between also nullifies any claim by the Agency that the entirety of the letters remain classified to protect sources or liaisons and no portion can be released. This leaves only the latter half of the exemption, which claims that the release of the materials, which describe CIA’s obstruction of GAO’s audits, would “impair the effectiveness of an intelligence method currently in use, available for use, or under development.”

The Agency’s claim that the release of the materials would be categorically harmful and no part of the letters can be released is entirely undermined by their inclusion of quotes from these letters within the very same file. This means that even if the information did need to be protected for sources and methods, the Agency has admitted that it could be segregated and redacted if necessary. In light of this de facto admission, their failure to do so negates any “good faith” claim the Agency has to completely withholding these letters. The decision to not release the letters and claim the entirety of it must remain classified is undermined by the excerpted portions.

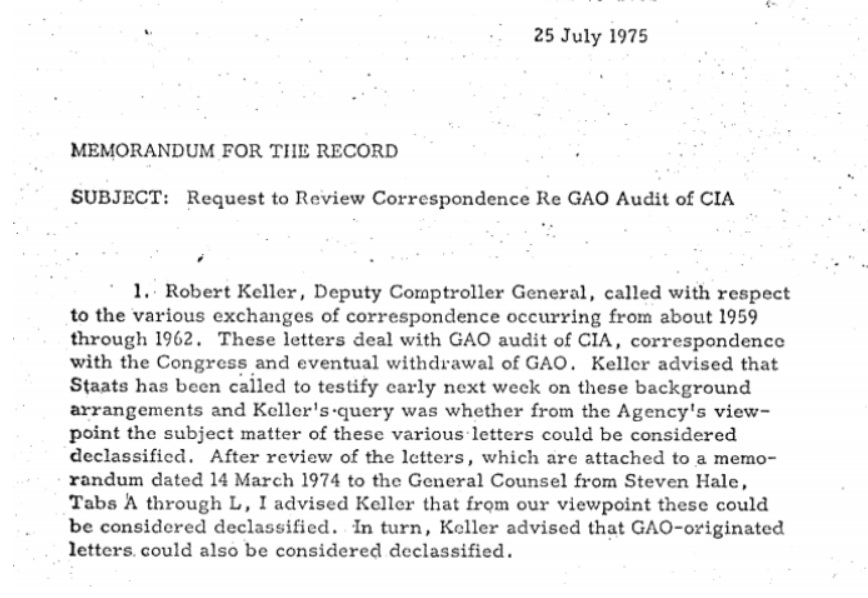

CIA’s decision to declare the letters as currently exempt from declassification, on the absurd basis of protecting sources and methods, no less, also flies in the face of CIA’s determination about the matter in 1975. A declassified letter, dated July 1975, shows that CIA’s General Counsel stated that they could be considered declassified.

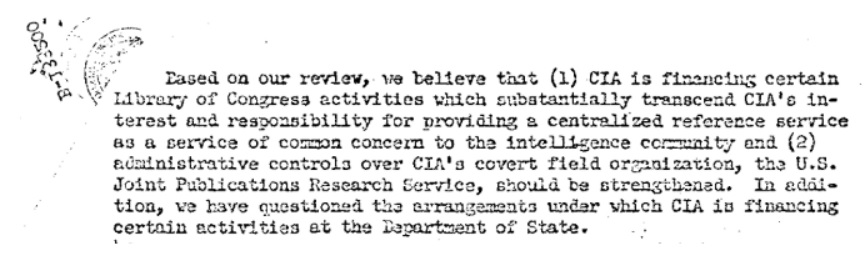

Most damningly, the Agency’s claim that the information is unreleasable contradicts the fact that it had already been released in a report that the President and CIA helped censor when it was made clear that CIA would not be allowed to rewrite the report. According to CIA, this same report revealed “concluded that the foreign intelligence budget was three or four times larger than Congress had been told” These letters, which CIA attempted to prevent from being re-released, raise additional concerns about CIA’s process of killing GAO audits. In addition to the fact that full GAO audits may well have allowed Congress to identify the illegal aspects of CIA’s MKULTRA program much sooner, the audits that GAO did perform highlighted concerns about the Agency’s activities and expenses. This pattern would continue into the 1980s and help enable the State Department’s CIA sponsored involvement in the Iran-Contra affair. As the Senate would later note, CIA stonewalled those later GAO investigations into domestic aspects of Iran-Contra as well. Significantly, as early as 1961 the GAO was noting that CIA’s funding of the State Department’s activities was questionable.

According to the letter, CIA had been “financing certain Library of Congress activities which substantially transcend CIA’s interest and responsibility” to the tune of $685,000 in 1961. The GAO also noted that “administration controls over CIA’s covert field organization, the U.S. Joint Publications Research Service” needed to be strengthened. also “questioned the arrangements under which CIA is financing certain activities at the Department of State” to the tune of nearly $2,5000,000 in 1961.

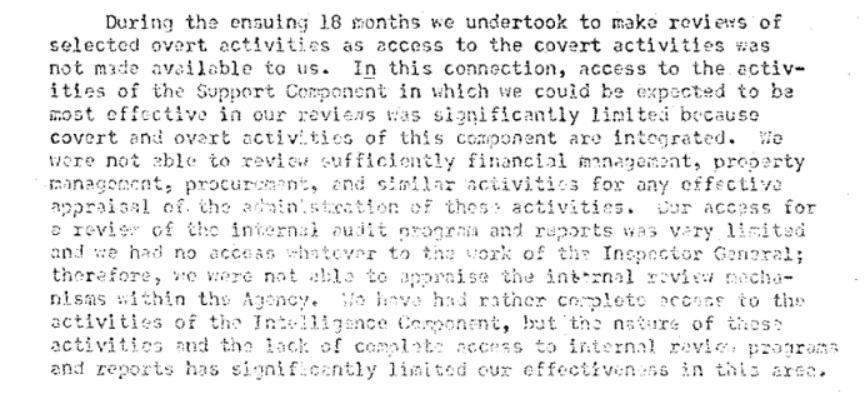

The letters also showed that the GAO had little to know access to materials from the Support Division or CIA’s internal audit programs and reports. Similarly, the GAO was denied all access to the work of the Agency’s Inspector General. As a result, they “were not able to appraise the internal review mechanisms within the Agency.”

A full review of the letters clearly shows that, despite CIA’s claims, no intelligence sources or methods were discussed, and that the release of the letters would not in any way negatively impact the Agency except by making it look bad.

While GAO audits of the Agency had been completely negated, the Agency’s problems with the GAO were only beginning. These problems would only serve to further call into question the Agency’s good faith as testimony and documents demonstrate that the Agency’s problem revolved not with security concerns, but with ones about oversight. Given the Agency’s belief that CIA should decide when to be subject to oversight, this is hardly surprising. The Agency’s continuing problems with GAO will be explored in additional articles. In the meantime, you can read a selection of relevant releases and redactions below. You can also read unredacted copies of the letters withheld by CIA here.

Like Emma Best’s work? Support her on Patreon.

Image via Wikimedia Commons