This May, far up the Eastern seaboard, in the tiny coastal community of Machiasport, Maine, frustration and disbelief erupted as they received news of Governor Paul LePage’s budgetary plans for their corner of the world. The 46 employees of the 1000-person town’s minimum security prison all received notice that they would be losing their jobs and the facility’s 100-plus population would be dispersed among the State’s other prisons or released into the world, tethered to the DOC by the use of electronic monitoring.

The legislature ultimately provided funding to keep Downeast Correctional Facility open - at least for a little while longer - but the situation raised a novel question about the appropriate use of GPS monitoring devices as an alternative to incarceration, particularly where local economics are concerned.

The use of electronic monitoring has been growing across corrections and immigrant detention, as law enforcement departments struggle to operate systems in which there’s more demand for jail beds than can be supplied or funded. In response to a nationwide MuckRock survey, the Maine DOC is one of six state DOCs that provided contract materials related to its use of Satellite Tracking of People (STOP), an electronic monitoring equipment company run by Securus, already the most popular company for corrections communications like phones and tablets.

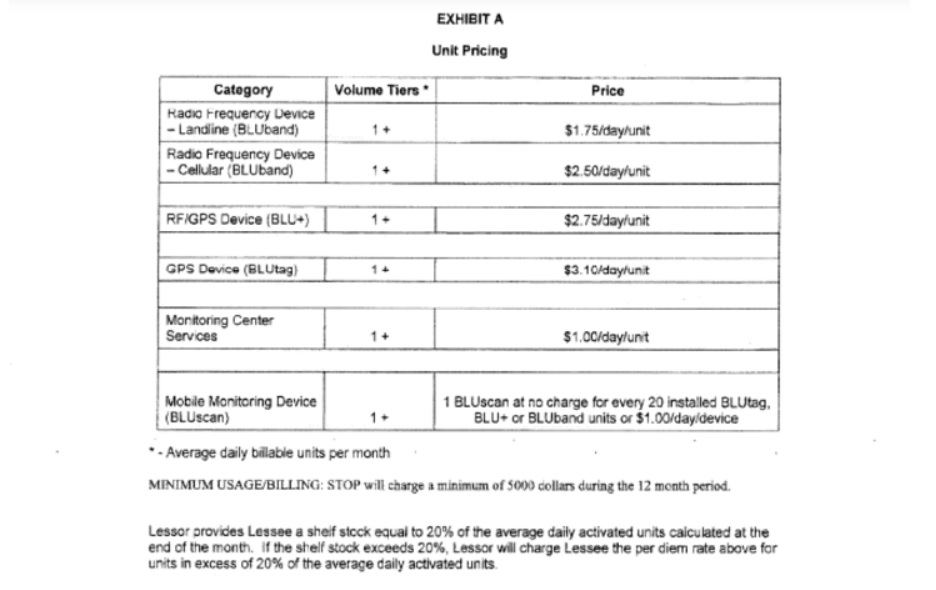

In materials released from Maine and South Dakota, which also employs the company for some of its populations, the pricing for equipment can range from $1.75 a day for house arrest bracelets to $3.10 a day for its GPS ankle monitor.

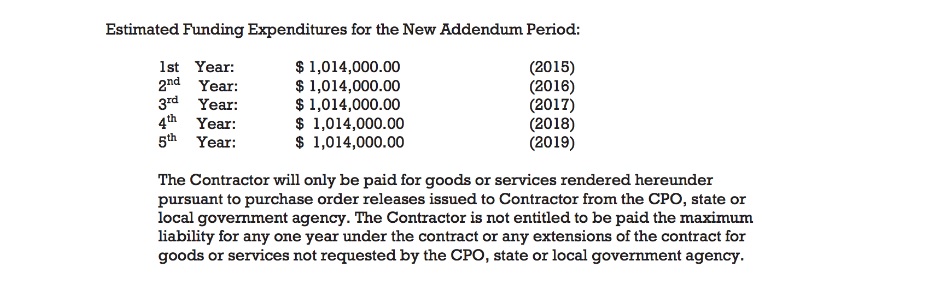

The place of electronic monitoring is still being as maneuvered in many areas. South Dakota budgeted for $25,000 a year, roughly enough money to monitor about twenty inmates for the thirteen months of the contract. Tennessee, on the other hand, which has a population over 7 times that of South Dakota, has allotted nearly 40 times as much money to its use of the equipment.

And while there arguments to be made for the relief a release-and-monitor system can provide to those awaiting trial, prisons suffering overcrowding, and families hopeful for the return of their loved ones, the charges being transferred to inmates and their support networks are sometimes comparably destructive, particularly when juveniles are involved.

Far across the country from Downeast Correctional Facility, California is considering a bill to prevent fees related to the monitoring of the non-adult population, a practice that has been burdening families beyond the stress of a jailed child. Such measures will likely become increasingly necessary as the industry pushes for the increased use of GPS equipment and citizens begin to experience the new challenges that technological solutions present.

MuckRock will be continuing to follow up with departments around the country. As always, let us know if you want an inquiry sent to a department or facility using electronic monitoring near you.

The California contract is embedded below, and the rest can read on their request pages.

Image via Wikimedia Commons and licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.