This part 1 of a 4-part series on private prison contracts, giving an overview of the current landscape. Part 2 can be read here.

At their last official weigh-in, Corrections Corporation of America and GEO Group, Inc. together held 175 correctional and detention facilities in cities and towns across the United States. Between immigrant detention facilities (also known as “family residential centers”), federal, state, and local prisons and jails of all security levels, youth residential and non-residential centers, and community corrections facilities, the two have bobbed and weaved themselves into a strong position within the American incarceration system.

In an interesting arrangement of the competitive field, however, their business strategy must both work with and profit against their challengers, almost as though they’ve placed bets on both sides. After all, they are almost entirely dependent on the contracts they sign with the government.

States with contracts with CCA

States with contracts with GEO

- Yellow = leased only

- Blue = facility managed

- Red = facility owned/operated

- Green = facilities owned, managed, and leased

- Purple = facilities both owned/operated and managed

By prison bed count, CXW and GEO (as they’re known on the ol’ Exchange) are among the top ten largest such systems within the whole country, contending with the likes of the Bureau of Prisons’ federal numbers and heavy hitter states like California and Texas, all top customers.

CCA and GEO may not be the only companies operating private for-profit prisons in the U.S., but their recent buying habits suggest that they soon may be. The two publicly-traded operations control the vast majority of the market share - by its own estimates, CCA alone holds 59 percent of all privately-owned prison beds in the country and GEO’s numbers make up most of the rest. (This doesn’t include GEO’s day reporting centers or their overseas operations but does include those facilities that are currently empty.)

For GEO, that means 79,912 beds, 73,217 of which are for adult or immigrant detention - for CCA, that’s 83,919 of 88,559 total beds. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 131,300 people were in private facilities at the end of 2014 (the report on Prisoners in 2015 has not yet been released), not including those held for Immigration and Customs Enforcement or other immigration facilities. For BOP alone, private prison beds hold about 20 percent of their 192,663 person population.

None of this would be possible without the injured operations being run by their main competitors.

Over and over, these agreements are tantamount to a government admission that it’s unequipped to deal with the situation, as they sign and extend contracts enlisting the services of what are now essentially real estate magnates with security services.

Private prisons are like the full package offering in a prison system that has historically relied on its relationships with private businesses for goods and services. Those relationships, too, are typically dictated by contracts that are also publicly available, because they’re technically signed with taxpayer funds.

Infographic via In The Public Interest

It makes sense that the government should be their biggest customers, as only the government really has the authority to incarcerate, making private prison companies dependent on their “government partners” for work. Fortunately for them, they foresee a bright future through their cash-colored eyes as long as state and the federal systems remain overcrowded to the point that a court may determine conditions to be “cruel and unusual punishment.”

CCA and GEO both operate as Real Estate Investments Trusts (which allows them to share a tax class with hotels). But it’s the management work - including the provision of officers, conditions and everything else that comes with it - that make their physical assets both useful and lucrative. That their business is tied to the needs of the government by the predictable nature of their contract-dependent relationship is an important selling point to shareholders. But, in terms of asking much from its employees, the government primarily holds the companies as just the sort of warehouses they need to deal with “first-things-first” matters of population control. And efforts to make them more than that are easily ground to a halt.

Just last month, a bill in Mississippi stipulated changes to the way that the state enters into contracts, including clauses requiring both a 10% savings over the State’s Department of Corrections costs and a recidivism rate 10% less than that of the DOC. It died in the House’s Committee.

If the Efficient Government Management fairy waved her wand today to abolish private prisons (like a certain Presidential candidate has advocated for), she’d have a lot of different considerations to run through in the time spent flicking her wrist. Assuming she takes some kind of bureacratic, by-the-books approach, at the very least, all of the contracts would need to be cancelled.

But she’d probably have to also deal with the reason we have them in the first place: more prisoners than capacity in the public prison system. This problem itself is just so complicated, involving a storm of circumstances: the socio-economic conditions faced by American individuals, our definitions and assigned punishments for criminality, and the practical inadequacies of the governmental systems tasked with maintaining the judicial scales. Part of the hard problem in addressing the big problem of MASS INCARCERATION IN AMERICA is that it’s built in bits and pieces by state and local systems during expansion.

So, short of solving the root causes of each jurisdiction’s incarceration overload, she’d then have to find somewhere to put the prisoners currently being held. And maybe she’d find some way of encouraging those inmates to avoid in the future whatever the path that otherwise led directly to jail, and maybe somewhere that rehabilitative approach could be used to nudge the public system toward a policy of prison as a one-time stop, if the detour has to be made at all. Of course, she’d have to find a way to keep paying for it.

And, if she were really trying to tie up all loose ends, she’d also do something about the towns hosting these private prisons now, often rural, where jobs and other incentives would be disappeared. Essentially, she would need to find a way to fill all the holes in the public system that private prisons are supposed to satisfy.

In her absence, private prisons are supposed to be something like our interim EGM Fairy, a stress valve for the strained system they’re meant to help, even while total success would mean their ultimate elimination altogether.

That’s a complicated series of incentives, which helps to show how important the contract terms are in determining precisely who is responsible to whom for what. Not all private prison contracts are created equal.

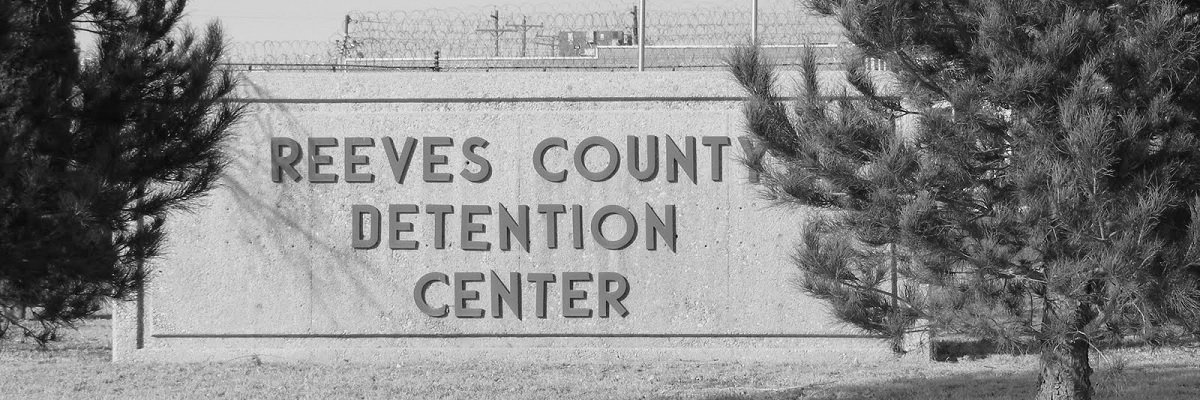

The field stretches across the American landscape from Live Oak, Calif., to Philipsburg, Penn., Eloy, Ariz., to Millen, GA. In particular, the South and rural areas have been natural targets; opposition comes less strongly in areas with little industry, where vicinity to the border or inflation in crime caused by poverty and lack of education have ballooned the demand for prison beds, the jobs they bring and the favorable tax rates offered.

- Corrections Corporation - Red

- GEO Group - Blue

- Management and Training Corporation - Green

Their prisons, detention centers and jails have been landscape staples in some parts since the 1980s, but CCA and GEO remain symbolic straw men for a government in cahoots with capitalist corruption of justice. The contract is the rallying point for the customer, the company and the opposition. Since contracts are the technical bread and butter of the industry, in filings for shareholders, companies acknowledge that their business depends on winning and losing these contracts and that a turn in public opinion can hinder their growth, as it has before.

But in California, where court-ordered reduction of overcrowding has made them a sure long-term customer, and Arizona, home of harsh sentencing laws and immigration laws, the reliance on private operators seems well-established, and it’s a practice that now sees global adoption as GEO Group operates in Australia, South Africa, and the U.K., the latter home to multiple other bigtime private security firms running similar incarceration operations.

So where does it begin, this public-private partnership? Check back in two days for part two, where we’ll look at how contracts get awarded in the first place.

Image via Pixabay