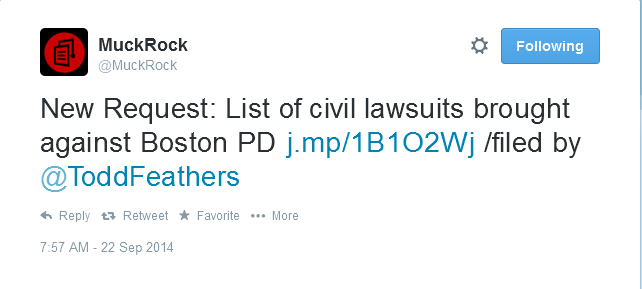

Just over a week ago, I filed a records request with the Boston city clerk for lawsuits brought against the Boston Police Department, and MuckRock tweeted about it.

MuckRock users, including myself, file numerous requests with Boston agencies, and most of them follow a normal trajectory - agency’s public records liaison, attorney review, and then back to our office.

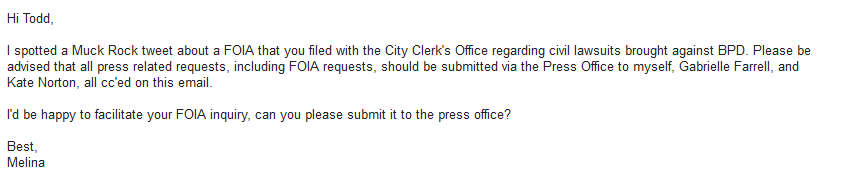

Several days after I filed my request, however, I received the following email from a press aide to Boston Mayor Martin J. Walsh:

“I spotted a Muck Rock tweet about a FOIA that you filed with the City Clerk’s Office regarding civil lawsuits brought against BPD. Please be advised that all press related requests, including FOIA requests, should be submitted via the Press Office … I’d be happy to facilitate your FOIA inquiry, can you please submit it to the press office?”

The mayor’s press office is not the agency that maintains the records I asked for. And according to Massachusetts law, “Every person having custody of any public record” shall provide it for inspection to members of the public “without unreasonable delay.”

When asked to clarify the policy for this story, Kate Norton, the mayor’s press secretary, said in an email that “There is no official ‘requirement’ for press-related FOIAs to come through our office.”

But 12 days after I filed my request, the city clerk’s office has not acknowledged it. Under Massachusetts law, agencies must respond to a request within 10 calendar days.

In her email, Norton makes a reasonable argument for why journalists should want press-related records requests to go through the mayor’s office.

“We are also tasked with the records retention piece of fulfilling a FOIA request, meaning after the FOIAs are filled for members of the media, we hang on to them for the required time period afterwards,” she wrote. This allows the press office to provide journalists with frequently requested records without the need to go through the usual, time consuming process.

But it also means that when asking for infrequently requested records, a journalist’s request must go through an even longer process.

“It just doesn’t make any sense, they’re adding another loop,” said Rob Bertsche, general counsel for the New England Newspaper & Press Association.

“The policy seems to contradict the spirit of Massachusetts’ public records statute, which is designed to facilitate the prompt production of records,” Bertsche added.

It also creates a double standard for journalists and other citizens.

“Almost everywhere in the nation, at both the federal and state level, you make requests to the governmental agency or department that has the records,” said Adam Marshall, the Jack Nelson Legal Fellow at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. “It’s very odd that members of the media would be treated differently that members of the public.”

Boston’s policy is not unique, although representatives for most cities contacted by MuckRock said they do not segregate records requests by journalists.

Jacksonville, Fla. uses a similar system to Boston. Journalists seeking city records may choose to submit their requests to a centralized location, where it is attorney Alexis Lambert’s job to see that the requests are filled.

“It’s not designed as a barrier to access, it’s just designed to make sure it gets done and completed,” Lambert said.

In general, she estimated, requests submitted to her are completed faster because fulfilling them is her primary responsibility.

That said, Mayor Walsh’s press office has a decidedly different responsibility.

While it is cynical to assume that the office is intentionally delaying requests for the purpose of stifling journalism, it is not unreasonable to assume that requests are being delayed because the mayor’s press aides are busy with other work. Or because the requests themselves are being analyzed for the story ideas that prompted them.

As Marshall puts it, “I would be concerned that they might be flagging certain requests by members of the media, and that can be problematic for various reasons.”

Image via Wikimedia Commons and is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0